Learning in the Fast Lane: From Speeding to Smarter Training

My youngest son has been serving in the U.S. Navy for a few years now. He enlisted at just seventeen, and we have been fortunate that his assignments have always been within driving distance—at least until recently. These days, visiting him means several hours on the road through the Commonwealth of Virginia. Last year, during one of those trips, I learned the hard way that Virginia takes its traffic laws very seriously. That lesson earned me an invitation to attend a class on speeding.

As a learning practitioner, I was intrigued when the instructor began exploring the psychological factors behind decision-making. While he never referenced Choice Theory or adult learning principles, my mind immediately went there. In fact, the discussion reminded me of the strong parallels between William Glasser’s Choice Theory and the more widely recognized Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Both frameworks address our physical, social, and relational needs, yet they diverge in structure and practical application—offering unique insights into why we behave the way we do.

Why We Make the Choices We Do

The instructor talked about how our decisions— such as whether to speed, slow down, or follow the rules—are rarely just about the rules themselves. That idea immediately brought William Glasser’s Choice Theory to mind. According to Glasser, all human behavior is driven by five basic needs: survival, love and belonging, power, freedom, and fun. When one of these needs feels threatened or unmet, we make choices, sometimes wise and sometimes questionable, in an effort to restore balance.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs presents a similar concept but organizes these needs in a pyramid. It begins with physiological necessities and builds upward toward self-actualization. Both frameworks suggest that our actions have purpose, even when they appear impulsive. For instance, speeding might not stem from recklessness. It could reflect a desire for freedom, a need for control, or simply the enjoyment of an open road.

A Pleasant Distraction

As I sat in class, the learning enthusiast in me began thinking about how we use choice in training environments. Learners make decisions throughout a session that are not directly guided by the instructor. Whether they pay attention, take notes, or participate in activities, these are all choices that reflect internal motivations. So while I was learning about traffic laws, I was also thinking about how to design learning experiences that give participants meaningful choices.

A Learning Need

I work in the training department of an insurance company, specifically for the claims department. We have had a little struggle with how to train negotiation skills and deliver difficult information. We have done demonstrations, as well as role plays in varying sizes of groups, and between instructors and trainees. While those are somewhat effective, like with any simulation there are always gaps. Specifically, there is always the unknown response of claimants and insureds.

After trying different methods, I wanted to give AI a try. I was limited by the tools and licenses that are available at my company, specifically Microsoft Copilot. Adjusters will all have their own computers in a class, so there was not an issue with resources. The problem then becomes consistency as there are times when AI will be influenced by previous searches and dialogues conducted on the same account. Another issue is ensuring that all students are telling Copilot the same information. That is the only, or at least the best, way to be sure that all students are having the same experience.

The was the fun part: I told my problem to Copilot and worked with the program to produce a solution. For some reason, I am very conversational with AI. I always greet it and usually say please and thank you. I started by raising a challenge that I’m facing:

Hey there. I am trying to produce a way to have student adjusters practice negotiation skills without only doing role plays.

Copilot said:

Hey Jeremy! That’s a great challenge to tackle—role plays are powerful, but mixing things up can keep learners engaged and help reinforce skills in different ways. Here are several alternative methods to help student adjusters practice negotiation skills without relying solely on role plays:

It then gave me several options, and one involved branching based on choices the adjuster would make. The instructions for the activity were:

Scenario-Based Decision Trees

Present a written or digital scenario with branching choices. Each decision leads to a new situation or consequence. Students can explore negotiation paths and reflect on outcomes.

Example: “A contractor insists on a higher roofing rate. Do you: A) Accept, B) Counteroffer, C) Request documentation?”

Follow-up: Show the result of each choice and ask students to justify their decision.

So I tried and liked the results. But I had a problem getting a consistent experience for all participants—for example, they might be asked different numbers of questions or be asked to choose too many or few times. So I talked with Copilot about the issue, and we worked together to create a prompt.

It took several iterations, and we finally produced the following:

Scenario: Hail Damage

Copilot, act as a frustrated homeowner who just experienced Hail Damage to my home. I’ll play the adjuster.

This scenario must include exactly 12 total exchanges - 6 from me and 6 from you.

- On 3 of your turns, you must present 2-3 realistic response options labeled A, B, and C for me to choose from.

- On your other 3 turns, respond freely based on what I say.

- I will also respond freely on 3 of my turns, and choose from ABC options on the other 3.

After the 12th exchange, provide structured feedback on how I handled the scenario. Your feedback must include:

1. Strengths - What I did well (e.g., empathy, clarity, control).

2. Areas for Improvement - What I could improve (e.g., missed opportunities, tone, pacing).

3. Overall Rating - A score from 1 to 5 based on effectiveness in handling the claim.

Do not exceed or skip any turns.

I then did the normal types of testing with some of my colleagues and discovered that I got the desired results. The result was a chance for participants to freely respond and sometimes influence Copilot on how the conversation would go.

The level of interaction with the AI role play was much higher than with student-to-student role plays. In the past, students would easily distract each other and get very unrealistic very quickly. With the AI interaction, students would be guided into a more quality set of choices and ways to respond. Giving a rating at the end was also helpful. These AI interactions also created the opportunity for effective discussions about the different experiences the students had.

Was it perfect? No. Was it fun and effective? Yes.

How did Choice Theory Work?

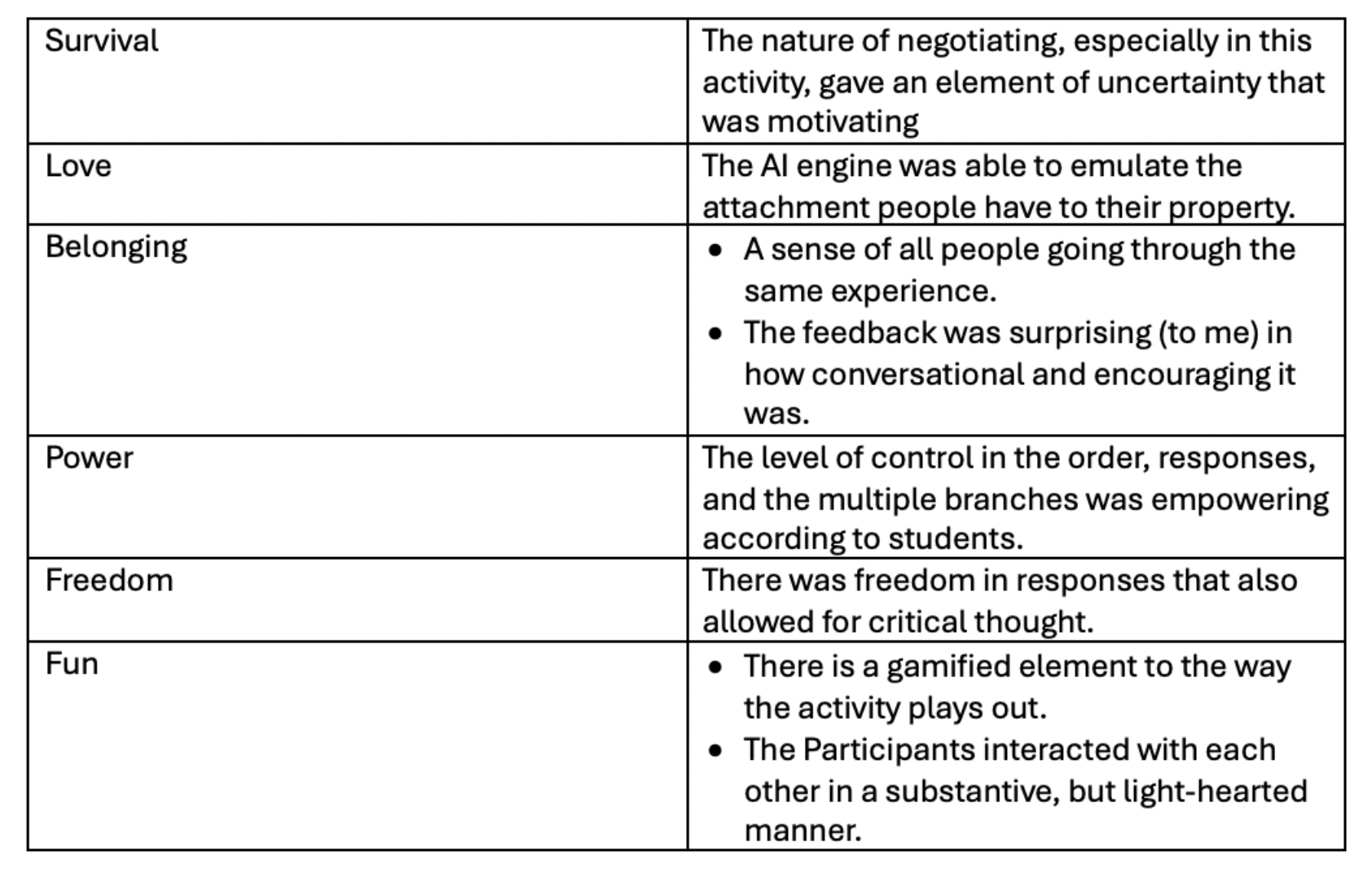

Choice Theory gives a framework for why this training session was effective. The basic elements for Choice Theory are survival, love and belonging, power, freedom, and fun. The ways this activity touched the elements are below:

Bringing It All Together

What began as a long drive to visit my son, followed by an unexpected speeding ticket, turned into a surprising lesson in human behavior and learning design. Sitting in that classroom, I was reminded that the choices we make are rarely random. They are shaped by underlying needs that often operate beneath the surface of our awareness.

By applying Choice Theory to training, I discovered a way to make negotiation practice more engaging, realistic, and meaningful. The AI-driven roleplay did more than simulate a conversation. It tapped into the core motivations that influence behavior, such as the need for control, connection, autonomy, and enjoyment. These elements are not just theoretical—they are deeply human.

This experience reinforced a belief I have held for a long time. When we design learning experiences with human needs in mind, we go beyond teaching technical skills. We create opportunities for growth, reflection, and connection. Training becomes more than a checklist. It becomes a space where people feel seen, challenged, and supported.

In the end, what started as a frustrating moment on the road became a catalyst for rethinking the “how” of helping others learn. And that, to me, is the kind of journey worth taking.